Growing Challenges to Internet Freedom

Next week, government, business, and civil society representatives will gather at the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) in Nairobi, Kenya to discuss

the future of the global digital space. This gathering takes place against the backdrop of growing restrictions by repressive regimes on online freedoms. The U.S. and European governments have undertaken significant initiatives to respond to these restrictions, but their initiatives are inadequate to stem, let alone reverse, the decline of freedom on the internet. Stronger action is needed.

Restrictions on the Internet

Even before the Arab Spring had shown the power of the internet to accelerate the free flow of news and views and to bring like-minded citizens together to mobilize for change, authoritarian regimes had introduced extensive controls over digital media. Authoritarian regimes had built pervasive, multilayered systems for online censorship and surveillance. These systems have grown more diverse and sophisticated in the past two years, as documented in Freedom House’s 2011 Freedom on the Net report and elsewhere.

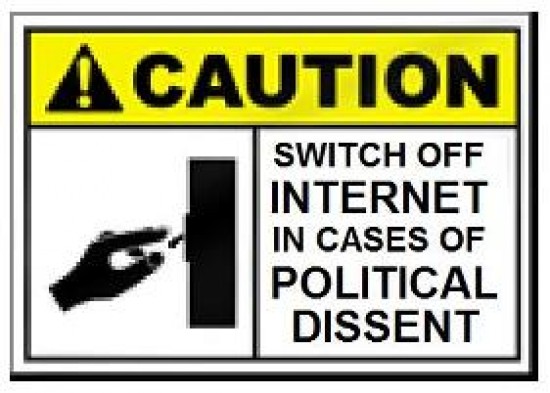

Governments increasingly resort to “just-in-time” blocking of online content or social media applications at critical moments, such as periods of unrest. Malawi’s government, for example, blocked access to news websites, Facebook, and Twitter in July as part of its clampdown on mass protests. Just-in-time blocking at times has affected a whole country’s internet. Access to the internet was cut off entirely in Egypt amidst the January 2011 mass protests calling on then President Hosni Mubarak to step down and in Libya in March 2011 as its leader, Muammar Qaddafi, tried to stem the anti-regime uprising. Moreover, government control of internet infrastructure is increasingly being used to insulate citizens from the global internet. Iran, for instance, is taking steps toward the creation of a national internet to disconnect Iranian users from the rest of the world.

Intermediary liability is on the rise as a method of censorship. Governments increasingly hold hosting companies and service providers liable for the online activities of internet users. In Vietnam and Venezuela, some webmasters and bloggers have disabled the comment feature on their sites to avoid potential liability. Governments also force businesses to police internet use. Belarus, for example, introduced requirements for Internet cafés to check the identity of users and keep a record of their web searches.

Online surveillance appears to have grown more extensive over the past two years. In Iran, for example, the government used intercepted online communications, including activities on Facebook and the Persian-language social media site Balatarin, to prosecute activists involved in protests against the fraudulent 2009 presidential election. Many arrested activists reported that interrogators confronted them with copies of their emails, demanded the passwords to their Facebook accounts, and questioned them about individuals on their friends list.

Digital attacks against human rights and democracy activists have become widespread. The pro-regime Syrian Electronic Army defaced Syrian opposition websites and spammed popular Facebook pages, including that of U.S. President Barack Obama, with pro-regime messages. Sophisticated cyber attacks have also originated from China. These included denial-of-service attacks on domestic and overseas human rights groups, email messages to foreign journalists containing malicious software capable of monitoring the recipient’s computer, and a cyber-espionage network, which extended to 103 countries, to spy on the Tibetan government-in-exile. In Belarus, to stifle protests against the fraudulent December 2010 elections, denial-of-service attacks slowed down connections to opposition websites or rendered them inaccessible. Moreover, the country’s largest internet service provider, the state-owned Belpak, redirected users from independent media sites to nearly identical clones that provided misleading information, such as the incorrect location of a planned opposition rally. Digital attacks on websites or blogs that are critical of the government have also taken place in several countries rated “partly free” on internet freedom by Freedom House, including Kazakhstan, Malaysia, and Russia.

International Support for Online Freedom

The U.S. and European governments have developed similar policies to promote internet freedom. These policies generally pursue the following aims:

Preserve open nature of internet: The U.S. and European governments have resisted attempts to place Internet governance under the United Nations, specifically the International Telecommunication Union, where authoritarian regimes may have greater scope to control online space. They instead support the multi-stakeholder bodies that currently govern the Internet, such as the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN).

Expand international recognition for key principles of free expression online: A wide range of democratic governments have agreed on the principle, as expressed by Swedish Foreign Minister Carl Bildt, that “The same rights that people have offline—freedom of expression, including the freedom to seek information, freedom of assembly and association, amongst others—must also be protected online.” This principle was reaffirmed and elaborated by United Nations Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression, Frank La Rue, in his report on Internet freedom to the UN Human Rights Council in June 2011.

Support digital activists: The Netherlands and Sweden have begun to fund programs to support bloggers and cyber dissidents who come under threat. They have also pushed for greater European Union funding for internet freedom programs. The U.S. State Department has supported a range of initiatives to promote digital activism and spoken out against the arrests of prominent bloggers, such as Bahraini “blogfather” Mahmood al-Yousif.

Circumventing online censorship

Fund anti-censorship technologies and digital security: The U.S. State Department has spent $50 million since 2008 on a range of Internet freedom programs and is about to receive $20 million more. These programs have included support for technologies to circumvent online censorship, secure mobile phone tools, efforts to reintroduce blocked content to users behind a firewall, and training for activists in digital security. (Freedom House’s internet freedom programs are funded in part by the U.S. State Department.)

However, U.S. and European policies on internet freedom have significant limitations. Restrictive internet laws and practices of authoritarian governments often go unchallenged. U.S. officials were largely silent, for instance, when Saudi Arabia introduced a requirement in early 2011 for online media sites, including blogs, to obtain a license to operate.

Voluntary codes of conduct

In addition, U.S. and European governments have looked to internet companies to adopt voluntary codes of conduct, particularly to sign on to the Global Network Initiative, to curb the use of U.S. and European technology to commit human rights abuses. Voluntary codes of conduct are, however, insufficient to prevent U.S. and European companies from assisting internet censorship and surveillance.

Even after Nokia-Siemens came under harsh criticism in the European Parliament for its sale of a monitoring center to Iran Telecom, several companies have supplied sophisticated surveillance technology to repressive regimes. Boeing subsidiary Narus sold technology to state-run Telecom Egypt to intercept and inspect internet and mobile phone communications. Britain’s Gamma International provided its product FinSpy to Egypt’s security service, which used the product to monitor dissidents’ online activities. This spyware infects the computers of dissidents and allows the security service to capture key strokes and intercept audio streams, even when the dissidents are using encrypted email or voice communications such as Skype. The Italian company HackingTeam has sold software to security agencies in the Middle East and North Africa that bypasses Skype’s encryption and captures audio streams from a computer’s memory. The French firm Amesys provided monitoring technology to Libya, which Muammar Qaddafi’s government used to intercept email and chat messages of dissidents.

Recommendations to Strengthen Internet Freedom

The growing restrictions imposed by repressive regimes are outpacing U.S. and European efforts to protect the space for free expression online. To expand that space, U.S. and European governments should build on their current policies with additional initiatives:

Challenge restrictive internet laws and practices: The U.S. and European governments should pursue joint, targeted initiatives to press for the removal of existing restrictions and to avert new restrictions that are under consideration. They should also develop an action plan to implement the recommendations of Mr. La Rue’s report, particularly to curb restrictions on internet content, criminal penalties for legitimate online expression, intermediary liability, infringements on online privacy, and cyber attacks. This action plan should be developed and implemented in collaboration with other democratic governments.

Loss of trade strong incentive for China

Address internet censorship as a barrier to free trade: The U.S. Trade Representative and the European Union have shied away from trade disputes over internet censorship. Although there are strong economic interests in avoiding such disputes, the United States and the European Union should challenge specific censorship practices under bilateral trade agreements with China and other countries and present a case against internet censorship before the World Trade Organization, because the potential loss of trade will provide a strong incentive for China and other countries to cut back on their censorship of online content and services.

Require transparency in sales and services to internet-restricting countries: American and European companies that come under pressure from authoritarian regimes to facilitate violations of human rights, for instance to filter online content or to provide access to private user data or communications, cannot be expected to stand up to such pressure on their own. They should be required to publicly disclose what products and services they provide to countries with extensive internet restrictions and what requests they receive from these countries to filter web content, turn over private data, or facilitate communications intercepts. Such disclosure would discourage technology companies from collaborating with internet censorship and surveillance and encourage U.S. and European governments to push back on such collaboration.

Export controls

Introduce export controls on censorship and surveillance technology: Voluntary measures are clearly inadequate to prevent the use of U.S. and European technology to violate human rights. Carefully crafted export controls are needed. These export controls should target specific technologies, such as content filters and spyware, that serve the primary purpose of limiting flows of online information or monitoring private digital communications. Dutch Foreign Minister Uri Rosenthal has called for export controls on filtering technologies, and the European Parliament voted in April 2011 to introduce export controls on technologies for monitoring mobile phone and internet use, but these export controls still require the European Council’s approval.

To advance internet freedom in the face of growing restrictions around the world, the U.S. and European governments cannot rely entirely on uncontroversial measures, such as advocating broad principles, criticizing flagrant abuses, and funding programs. They need to take bolder actions that directly challenge vested interests at home and abroad. Such actions are vital to reverse the global trend toward greater suppression on internet freedom.

Daniel Calingaert is the Deputy Director of Programs at Freedom House

December 12, 2011 at 11:17 am

hello to “www.lankastandard.com”-ers just sighned in, yous ok ????

steve pearson