The Sri Lankan Case: Rhetoric, reality and next steps

The last few weeks have witnessed increased activity by the Government of Sri Lanka inannouncing various measures recently taken and to be taken to strengthen

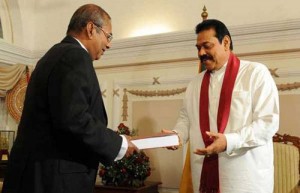

Head of the LLRC Mr. C.R.De Silva hands over the final LLRC report to President Rajapakse at his official residence Temple Trees on November 20th 2011

human rights,peace and reconciliation in Sri Lanka including the implementation of some interim andfinal recommendations of its own Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission(LLRC) issued in September 2010 and November 2011, respectively. Any genuine effortto address human rights, governance, a political solution and reconciliation is welcome.

Yet the suddenness of such statements raises questions of timing and the genuine will of the Government. They should be seen against the backdrop of the impending resolutionon Sri Lanka at the 19th Session of the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC). The heightened activity raises the question as to whether these measures are yet anotherploy to distract its critics from the absence of a real plan of implementation for the LLRC recommendations. This short note looks at GOSL rhetoric and demonstrates the fundamental flaws in thestructure of government in addressing human rights violations and accountability issues,the failures of past domestic processes and the need for immediate action by theinternational community.

Government’s Rhetoric and Ground Realities

The Government has argued for a homegrown solution. In the lead up to the UNHRCsession, the Government also requested more time in order to implementthe LLRCrecommendations. The Government’s position must be considered inlight of pastexperiences, progress made with other domestic processes and the contention that timealone can address grievances. The Government’s positionthat more time is needed mustbe contrasted with other practices where the Government has moved swiftly, such as thepassing of urgent bills, which is a regular practice used to enact legislation with limitedconsultation and transparency. Such practices confirm efficiency on the part of theGovernment when there is political will, raising the questionas to why there is a delay inthe implementation of the recommendations of its own commission. The questions below demonstrate that the call for a domestic process fails to addresssome key questions and concerns. The inability to address these can hamper any futureprocess for justice, accountability and reconciliation.

• What is the status with respect to the implementation of recommendations madeby past commissions of inquiry and committees? (see annexure)

• Why has there been no significant progress with the LLRC’s own interimrecommendations issued 18 months ago? The delay can be contrasted by thespeed with which the Government introduced urgent bills such as the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which was enacted within a few days.

• Following the submission of the LLRC report to Parliament, why has theGovernment not sought to initiate public discussions regarding the findings of the LLRC and have the full report translated into Sinhala and Tamil? Why hasthe Government not made public a road map for implementation, 4 months afterreceiving the report?

• How can any domestic investigation be independent in the present context whenappointees to independent institutions (including the National Human RightsCommission and Attorney General) are by the Executive as provided under theEighteenth Amendment to the Constitution?

• Can witnesses and victims feel confident about providing evidence to any domestic process in the absence of a functioning witness and victim protection mechanism?

• How can the Attorney General’s Department be expected to initiate independentinvestigations and indictments when it falls within the purview of the Executive?

• Why has the Government not submitted the NHRAP to Parliament? Recently the Government announced the creation of a committee to monitor the implementation of the NHRAP, more than 5 months after it was approved. Why was there a delay to commence implementation of the Government’s ownNHRAP?

• How can the proposed Parliament Select Committee (PSC) be considered a genuine effort to provide for a political solution? This is in light of the lack of progress made with the findings of the Government’s own All Party Representative Committee (APRC), which provided a consensus report in 2010to which the Government has not yet responded to, and the 18 rounds of bilateral talks held between the Government and the Tamil National Alliance(TNA) in 2011-2012.

Past commissions and committees appointed by the present government (see annexure)demonstrate the long list of entities appointed, but with no tangible change on theground. The experience of the International Independent Group of Eminent Persons(IIGEP), invited by the present government to observe a local commission of inquiry,confirms that merely having an international presence for a local process will not work inthe present political context. The final report of the IIGEP found a ‘lack of political will to support a search for the truth’, highlighting the present dilemma faced by domestic processes and a problem likely to be faced by any future entity unlessfundamental systematic flaws are addressed.

The Need for Action

A common element for any action by the GOSL in recent times is directly linked tointernational pressure and as a result the role played by some international actors cannot be discounted. The LLRC is one such example. The present call for a resolution withinthe UNHRC on Sri Lanka has provoked a torrent of promises by the Government of SriLanka – the most recent being the promise to enact a witness protection bill, which wasa promise first made as far back as 2007 by the then Minister for Human Rights andpresent envoy on the same subject, Minister Mahinda Samarasinghe.

Recent weeks have also witnessed an unprecedented level of advocacy in Geneva and key capitals withsignificant resources spent merely to keep the international community at bay, eventhough those resources could have been better spent on addressing the growing problems within Sri Lanka.

Civil society in Sri Lanka has witnessed countless years of violence and missedopportunities to address lasting peace and reconciliation. Worthless promises anddelaying tactics by the Government of Sri Lanka reinforce the culture of impunity rather than actually addressing the problems on the ground. Many domestic processes havebeen established during the period of this Government (refer to annexure) but with noimprovement to human rights protection on the ground. In light of the long list of faileddomestic entities and the lack of genuine progress, it is imperative to revisit the UNHRC.

The joint statement at the end of the UN Secretary General’s visit to Sri Lanka in May 2009 sets out specific pledges including the agreement by the Government to addressaccountability issues.The 11th Special Session of the UNHRC in May 2009 missed theopportunity to address human rights and humanitarian issues in Sri Lanka.

The inability of the UNHRC and its members to address human rights violations in 2009 can andmust be corrected now. Member states and others of the UNHRC need to critically examine the violations, culture of impunity and inability to have an independentdomestic process in a highly politicised and militarised Sri Lanka. It is time for theUNHRC not just to discuss the human rights situation in Sri Lanka, but also to examine ways of supporting Sri Lanka and its citizens achieve a lasting peace.

See original statement here

– CPA-