Use conciliatory diplomacy to deal with US-sponsored resolution

The US-sponsored resolution on Sri Lanka was formally presented to the 19th session of the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva last week. The confidence that the Sri Lankan government had evinced that its diplomacy would

UN Human Rights Commissioner Navi Pillay says she hopes the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) will address reports on Sri Lanka.

prevail and the resolution would be removed from the agenda did not materialize. However, the draft resolution presented by the United States differed in a significant area of its concern from the previous draft that had been in circulation. The present draft no longer specifies the issue of serious violations of international law and prosecutions for them as in the previous draft. Instead it seeks to provide for an international role in monitoring the implementation of the resolution and specifically calls on the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to “present a report to the Council on the provision of such assistance at its 22nd session.”

However, even this revised resolution has met with opposition from a wide range of non-Western countries, including Philippines, Egypt and Thailand. On the face of it the draft resolution before the Human Rights Council is a mild and moderate one, as indeed has been pointed out by several of the countries, including Poland, Australia and Denmark that have publicly announced that they will be supporting the US-sponsored resolution. While the draft resolution continues to refer to accountability for human rights violations, its central focus are on the findings and recommendations of the Sri Lankan government’s own Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission and their implementation.

As the LLRC was a government-mandated one with its commissioners handpicked by the government it can be taken for granted that its analysis and recommendations will not be biased against the government. Even if critical observations have been made by them they are likely to be in the best interests of the country, and also of the government, to the extent that the government has the best interests of the country in mind. If the government approaches the US-sponsored resolution in this spirit, reaching agreement with the United States and other co-sponsors of the resolution should not be an impossible task.

Now that the resolution is amended it may be easier for the Sri Lankan government to seek an accommodation with the sponsor and co-sponsors of the resolution. As stated by US Ambassador to Sri Lanka, Patricia Butenis, no

Sri Lanka’s Ambassador to the UN in Geneva Tamara Kunanayakam reportedly told the 19th session of the UNHRC March 9, 2012 that external threats persist despite the progress on the ground and urged the Council that if it is to remain credible it must give equal attention to economic, social and cultural rights as to civil and political rights and also to the collective dimension as to the individual dimension, to the international and the national.

government can be expected to cooperate in its own indictment in the case of grievous charges. The Sri Lankan government also has had a strong case against the selective approach to alleged war crimes in the context of the global war against terrorism and the actions taken by countries to eliminate the terrorists.

PREVIOUS EXPERIENCES

There are two previous occasions on which Sri Lanka faced international intervention on human rights issues. The first occasion was in 1991 shortly after the suppression of the second JVP insurrection after a ruthless anti terrorist campaign by the then government that led to an estimated 60,000 deaths. At the close of that war, almost the entirety of the JVP leadership was killed in a manner similar to that of the LTTE leadership. As in the case of the post-LTTE period, the aftermath of the crushing of the JVP saw a continuation of the some of the

practices of the anti terrorist war being used to intimidate the opposition and dissenters.

In the aftermath of the JVP insurrection international pressure mounted on the government headed by President Ranasinghe Premadasa to restore the rule of law and end the culture of impunity that had set in. Along with criticisms and condemnations of the Premadasa government there was a threat of economic sanctions. At that time in the context of a report on human rights violations, Amnesty International made 32 recommendations for human rights safeguards to the Government of Sri Lanka in October 1991, 30 of which the government accepted. Following its first visit to Sri Lanka in 1991, the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (UNWGEID) also made a series of recommendations, all of which the government accepted.

The second occasion in which international human rights organizations intervened in Sri Lanka was in 2007. This followed the killings of five young students from prominent families on the beach in Trincomalee and of 17 aid workers of an international humanitarian organization in Mutur. The government responded to the international pressure for an independent probe on these and other instances of human rights violations by obtaining the services of an Independent International Group of Eminent Persons (IIGEP) to assist a Commission of Inquiry appointed by the President to go into 16 such incidents.

However, the relationship between the international expert group and the Sri Lankan commissioners soon become contentious and unworkable. Eventually the whole exercise came to naught. The eleven-member group who consisted of representatives from India, France, Indonesia, the United States, the Netherlands, Bangladesh, Canada, Cyprus, the United Kingdom, Australia and Japan, abandoned their efforts and left in acrimonious circumstances. The report of the Commission of Inquiry they sought to assist never saw the light of day after it was handed over to the President. It would be no exaggeration to say that the failure of this endeavour to put a check to the culture of impunity has contributed in substantial measure to the present crisis.

HOMEGROWN SOLUTION

The US-sponsored resolution being promoted in Geneva at this time will be the third occasion in which there will be direct international intervention in an area of human rights. Apart from calling on the Sri Lankan government to implement the LLRC recommendations, the draft resolution has provision for setting up an international mechanism in Sri Lanka to provide the government with technical assistance and advice. This is an issue of the

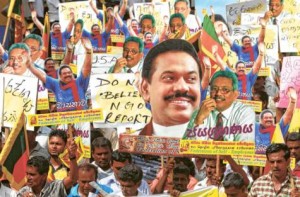

Supporters of Sri Lanka’s President Mahinda Rajapakse during a government sponsored protest against a draft UN resolution on alleged human rights abuses in Colombo late February 2012. There were widespread reports by human rights groups of people allegedly being forced to participate in this protest.

greatest concern to the government as it sees in this international intervention an infringement of its sovereignty. In coping with this challenge it would be well for the government to reflect on the two previous experiences in handling international human rights interventions.

It is important that any international mechanism that is set up to protect and promote human rights should draw upon the lessons of the past. The departing IIGEP submitted a report to the President in which they blamed the government for the absence of will to inquire into gross violations of rights and to ensure respect for the norms of justice and human rights. They gave the following reasons for their decision to quit: conflict of interest in the proceedings before the Commission, lack of effective victim and witness protection, lack of transparency and timeliness in the proceedings, lack of full co-operation by State bodies, and lack of financial independence of the Commission. On the other hand the relative success of the Amnesty International intervention of 1991 may be attributed to the preparedness of the Premadasa government to cooperate with the international community.

Interestingly, the two out of 32 Amnesty International recommendations for human rights safeguards which the government rejected in late 1991 were both concerned with impunity: the government refused to permit a Presidential Commission of Inquiry into Involuntary Removals to investigate “disappearances” which occurred before 11 January 1991, and refused to repeal the Indemnity (Amendment) Act, claiming it was no longer in force. Nevertheless what is significant is that the government of President Premadasa entered into dialogue with Amnesty International and implemented most of the recommendations even in an incomplete way. As a result the crisis was averted and Sri Lanka was soon restored to a relatively good standing with the international community and donor agencies.

Ultimately, human rights in Sri Lanka will best be protected by Sri Lankans themselves and not by the international community. The government and people of Sri Lanka need to take strength from the fact that the countries that are supporting the US-sponsored resolution in Geneva are giving a central place to the findings of the country’s own Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission. Sri Lanka should not be confronting the United States and other co-sponsors of the Geneva resolution but should be joining them in crafting a mutually agreeable resolution and mechanism for monitoring that gives pride of place to a home grown solution. Consultation, compromise and consensus, articulated by President Premadasa, would generally be the better way to resolve disagreements.

March 15, 2012 at 7:00 pm

The purpose of fighting the UNHRC and the US Resolution is with one

and only aim – to prepare the way and maintain local political power

among its naive voters!! Without it, there is no base.