Whither Sri Lanka after four decades of being a Republic?

“Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely” – Lord Acton (1834-1902) Letter

This column dedicated to the notion of fulfilling the aspirations of Sri Lankan society turns its spotlight on the aspirations of Sri

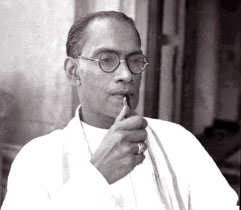

Forty years ago this week, at the auspicious time of 12:34 p.m. at the Navarangahala on 22nd May 1972, a new constitution was signed into law, creating the Republic of Sri Lanka. Photo shows then Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike

Lankans to be governed by a constitution that is geared towards ensuring a happy existence in Sri Lanka.

A discussion was held on 31st May 2012 at the N.M.Perera Centre in Colombo 8 by the Socialist Study Circle where the political scenario in Sri Lanka after forty years of being a Republic was analysed by Panelists, Constitutional Expert Dr.Jayampathy Wickremaratne PC and Mr.V.T.Thamilmaran Dean of the Faculty of Law of the University of Colombo. The present article is based on the matters discussed therein incorporating the writer’s views on the subject.

The Republic

Forty years ago at the auspicious time of 12:34 p.m. at the Navarangahala on 22nd May 1972, a new constitution was signed into law, creating the Republic of Sri Lanka . This was first republican constitution of Sri Lanka and the period 1970-72 during which it was created seems very different from the present considering the vast changes that have taken place in the constitutional history of Sri Lanka since then.

Social change

It was by this Constitution of 1972 for the first time in the history of the island that the republican form of state was established, Both of Sri Lanka’s two republican constitutions were created in the 1970s as the Second Republican Constitution came in to force in 1978 and is the present Constitution of Sri Lanka. In the Developing World, it was the era of anti-colonialism and nationalism, of non-alignment and nationalisation. Marxism-Leninism was considered at that time seriously as a viable prescription for the political and economic organisation of newly independent states, and revolution as the instrument of social change.

Executive Presidential system swollen with power

In the first forty years the republic faced insurrectionary and secessionist challenges to its mainstream political system. Since the 18th of May 2009 the military phase of Sri Lanka ’s ethnic conflict has been terminated. There has been extensive debate about what is and what ought to be Sri Lanka ’s post-war constitutional, political and societal disposition during the past three years. During this period the Executive Presidential System has acquired additional powers after the enactment of the Eighteenth Amendment to the 1978 Constitution making the Executive President to gain almost absolute power, such as which was enjoyed by the monarchs of yore. Lord Acton’s statement given at the outset appears to be true from the experience gained by the Sri Lankans under this system. This absolute power dominates the institutional structure and political culture of the Sri Lankan state The concepts of sovereignty, democracy, citizenship, pluralism, nationalism, secularism, and the constitutional form that preserves its unity in diversity of the Republic which gave rise to the need for constitutional change four decades ago appear to be limited to their names only at the present time.

Severing links with the Brisitsh crown

The idea that Ceylon should become a republic, and sever the constitutional links with the British Crown that had survived the grant of independence as a dominion in 1948, had been gaining ground in Sri Lanka for some time before the 1970 general election. It was

a consistent demand of the Left Wing Political Parties from before 1948, and after the populist-nationalist upheaval of 1956, S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike appointed a Joint Select Committee of Parliament to consider ways of revising the constitution which included the establishment of a republic. The idea of the republic within the Commonwealth established by an elected Constituent Assembly had already been founded by India in 1950. The alliance of the Left Wing Political Parties with the SLFP from 1964 onwards, in government (1964-65) and in opposition (1965-70), both emphasized the need for constitutional reform and made the possibility of a democratic mandate for creating a republic a reality.

Section 29

Due to the analysis of the scope and content of Section 29 of the Soulbury constitution made by British judges in the Privy Council in several cases of the 1960s, in which it was suggested that the anti-discrimination provision was absolutely un-amendable, even by a two-thirds majority a legal question arose as to the proper means of constitutional reform.. The Privy Council in London was then the final court of appeal for Ceylon , and as such, the final adjudicator of constitutional questions under the Soulbury constitution. Section 29 was the main minority protection mechanism of the Soulbury constitution, which constitutionally restricted the Parliament of Ceylon from enacting legislation having the effect of discriminating against any ethnic or religious community.

Two thirds majority

Under section 29,the procedure for constitutional amendment required essentially three components: a two-thirds majority in the House of Representatives; a simple majority in the Senate; and a certificate from the Speaker that the requisite two-thirds had been obtained in the passage of the amendment bill. In the August 1968 House of Representatives debate on the motion to reappoint the

Joint Select Committee on the Revision of the Constitution, the two positions on this matter were clearly enunciated by Dr Colvin R. de Silva for the opposition, and by the Minister of State J.R. Jayawardene for the government. Jayawardene’s position was that in spite of the Privy Council’s views, the wording of Section 29 (4) was clear to the effect that any part or all of the constitution was amendable by the Ceylon Parliament, provided the procedural requirement of the two-thirds majority was obtained.

Constitutional Assembly

Dr de Silva adverted to the same Privy Council cases in making his argument that the Parliament of Ceylon did not have the power to amend certain parts of the constitution, specifically the anti-discrimination provision in Section 29 (2). He stated that while he did not approve of the implications of the Privy Council judgments in terms of Ceylon ’s sovereignty and independence, he had no choice but to agree that the Privy Council’s observations to the effect that Section 29 (2) was un-amendable reflected the correct legal position. Therefore it was only through a process that was completely divorced from the fetters of the Soulbury constitution and of its amendment procedure that the people of Ceylon would be able to exercise their sovereignty in enacting a truly independent republic. Although the Indian Constituent Assembly served as the inspiration for Ceylonese Constituent Assembly which finally created the 1972 Constitution, the scrupulous attention paid to widest possible representation and rigorously negotiated consensus in India does not appear to have been considered in making the Sri Lankan Constitution.

Democracy is the rule of the multitude and does not often result in justice being done

As Plato said in his celebrated work ‘The Republic’, democracy is the rule of the multitude and does not often result in justice being done as in the execution of his friend and teacher Socrates it was the majority decision that was taken. The crucifixion of Jesus Christ was the result of the majority demanding the release of a criminal and the execution of a saint. This indicates that the majority decisions may not be right and just. Speaking of the ruler of a Republic, Plato said that such a ruler must necessarily be a philosopher. A philosopher must combine in his nature good memory, readiness to learn, breadth of vision and grace and be a friend of truth, justice courage and self control.

Limit powers

As such rulers are rare, the power given to a ruler should be limited. He further said: ’If you get in public affaires, men whose life is

impoverished and destitute of personal satisfaction, but who hope to snatch some compensation for their own inadequacy from a political career, there can never be good government. They start fighting for power, and the consequent internal and domestic conflicts ruin both them and society.’(See Page 264 Plato The Republic Tr.Desmond Lee Penguin Classics1987).

I leave it to the readers to consider the truth of this statement from the present Sri Lankan experience of men in politics. The recent incidents in Kolonnawa, which left one politician dead and the other seriously injured, come to mind. Although the left wing political parties voted for the Eighteenth Amendment which enhanced the powers of the Executive President it was the majority view of the Left that as stated in the Mahinda Chintana the Executive Presidency should be abolished as it concentrates excessive power in one person. Although the 1972 Constitution prohibited the promulgation of discriminatory legislation it revalidated all existing legislation some of which were discriminatory in nature.

The Constitution should have stated that such laws ought to be read subject to the provisions of the Chapter on Fundamental Rights which prohibited such legislation. Aristotle speaking of the Constitution in his work ’The Politics’ said: ’We must now discuss the constitution itself and ask ourselves what people, and what kind of people, the state ought to be composed of if it is going to be blessed and have a well run constitution. The well being of all men depends on two things; one is the right choice of target, of the end to which action should tend, the other lies in finding the actions that lead to that end. These two may just as easily conflict with each other as coincide.’(Aristotle The Politics Tr. T.A.Sinclair Penguin Classics at page 427).Aristotle held that the constitution must be geared towards the happiness of the people who are governed by it. Thus the time has now come to either revise the present Constitution or replace it with a new constitution geared towards providing happiness to our people.

Excessive power

The excessive power placed in the Executive President has undoubtedly affected the sovereignty of Parliament and has made it a subservient body to the President, which is detrimental to the preservation of good governance and the maintenance of the Rule of Law. The placement of the Attorney General and the law officers of the State directly under the control of the Executive President was another step in the wrong direction as this affects the independence and the freedom of action of such officers. Let all Sri Lankans hope and pray for the rectification of these errors and that Sri Lanka would soon be blessed with a new constitution acceptable to all races of our land thereby fostering racial harmony and happiness among all the Sri Lankans.

As usual let me conclude with an amusing anecdote. A Sri Lankan politician who had just undergone a very complicated operation kept complaining that he could feel some sort of bump on his head and that he had a terrible headache. Since the operation had been to his stomach, these were not the type of side effects that the nursing staff had anticipated. Fearing that the politician must be suffering from post operative shock, one of the nurses mentioned the symptoms to the surgeon. who had carried out the operation. ”Don’t worry” said the surgeon, ’he really does have a bump on his head as halfway through the operation we ran out of anaesthetic.”